About Edward William Miller

Ruth (Miller) Collings, one of our father's first cousins, gave me a copy of a 12-page manuscript her father had written of his growing up years (1890s) in Eagle Lake Township, Otter Tail County, near Ashby, Minnesota. This is an excerpt from his manuscript, written from memory in 1960. Any words within square brackets were added later, by me, in the editing process. --Jerrianne (Johnson) Lowther

On November 1, 1960, Edward W. Miller wrote:

At the request of my children, I am making an attempt to write a history of my life, going as far back in my childhood as my memory will take me. I have no diary so must depend entirely on my memory, hit only the high spots as they come to mind, and make a guess as to dates.

FAMILY

by Edward W. Miller

Ontario, CA

I was born January 9, 1882, near the town of Ashby, Minnesota. The country was new, with not too many settlers and still many opportunities to homestead land. There was also what was called school land that could be bought. To the east were a few Norwegians and to the west was a settlement of Swedes. About 30 miles to the south a few Germans had located. That was quite a distance in those days, and we did not see very much of them.

My parents were both of German descent. My father [August Miller] came to America when he was quite young. If my memory is correct, Father first came when he was 14 years old and then returned to his native Germany. Later, he came back. It is quite probable that Father entered the United States through a southern port. As a very small child I heard him tell of various places he had been in the southern states.

From what my mother told me, it seems that Father ran away from home to come to America. [It seems likely that he wanted to avoid conscription into the Prussian Army ... two of his uncles had already died in battle.] Mother told me that his parents were quite well to do. His only sister inherited the estate, which may have been the reason he was always reluctant to talk about his family and childhood.

My mother's maiden name was Emma Neller. She was raised in southern Minnesota. Her parents were born in Germany but emigrated from there to Wisconsin and then Minnesota. They located on land about 11 miles north of Austin. The land was covered with native timber that had to be cleared away before crops could be planted.

I well remember Grandfather [Joseph] Neller's first house built of logs. My daughter Ruthie and I each have a small bowl that I turned [on a lathe] several years ago from a piece of one of the old logs that was saved when the house was torn down.

I was about 10 years old when a new and much larger house was built. By that time, most of the timber had been cleared off, and the land was under cultivation, with the exception of a few acres of grove that had been retained around the farm buildings for shelter. The trees were mainly oak, and one year they became infected by worms, and every one died.

How my father and mother first met, I, of course, do not know. I presume in his travels to see the country, Father finally landed at my grandfather's place [Udolpho Township, Mower County, about 11 miles north of Austin, Minnesota] and very likely was in need of a job.

In this way they got acquainted, finally married [on December 25, 1880], and then moved to northern Minnesota where Father bought a little country grist mill. It was located about seven miles from Ashby, which was the railroad station on the Great Northern. This was probably about 1880. Father was soon joined by my Uncle Ed [Edward Neller] as a partner in the mill.

Although the author says he didn't know where his father learned the milling business, Ruth found the answer in the History of Otter Tail County Minnesota, published by B.F. Bowen & Co. in 1916. It contains an interview with August Miller on pages 899-900. Click here to read it.

I have no idea where Father learned the milling business, but I was told that he was a very good judge of wheat. Farmers would bring their wheat to be exchanged for flour. I very well remember seeing him open up the sacks, examine the grain and then tell the customer how much he would have to dock it because of dirt and other defects. He would then figure out a certain number of pounds of flour, bran and "shorts" [a by-product of wheat processing that consists of germ, bran, and coarse meal or flour] that he would give in exchange. There would be a certain portion that was retained for the expense of milling and profit.

The surplus flour was put in 25, 50 and 100 pound bags and shipped by railroad to be sold. This had to be hauled by team and wagon the seven miles to the railroad station at Ashby. There were times in the winter when the dirt roads were bad, and it would be impossible to make delivery to the station.

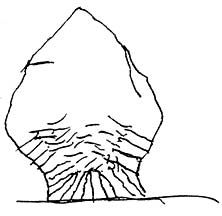

In those days the wheat was ground into flour by passing through and between large, flat stones. I was too small to know much about the process. I can just remember seeing my father lying on one of those stones, carefully pecking away with what seemed to be a sharp pointed tool. Undoubtedly, he was re-dressing the surface that had worn too smooth. Later, more modern equipment replaced the old stone process.

Jacob Collings with his great, great grandfather's grinding stones.

[These grinding stones were made in Belgium and may be seen today in the museum in Elbow Lake, Minnesota. Long after the mill burned down, a neighbor, Ed Fuglie, learned that they were about to be turned into stepping stones to a home near Battle Lake, Minnesota. He rescued the millstones and gave them to the historical society for the museum, according to our father, Donald B. Johnson. Jacob Collings, the child in the photo is Edward Miller's great grandson and August Miller's great, great grandson. The photo was taken by his parents at the Elbow Lake Museum and sent by his grandmother, Ruth Miller Collings.]

Minnesota is known as the "Land of Ten Thousand Lakes." Actually, I believe there are over 11,000. The mill was powered by water that came from lakes located at a higher elevation. The water was brought down through an underground flume that came to the surface about 25 feet from the corner of our house.

At that point, there was an open tank-like spot where a weir could be dropped to hold the water back when the mill was not operating. Fish (mostly black bass) would gather at this point, and it was an easy matter to get fresh fish anytime, right in the front yard.

From this point, the flume continued above ground to the mill that was located at a much lower point. Here the water entered what was called the penstock, at the bottom of which was located the waterwheel that furnished the power.

Some years there would be much rain, and the water in the lakes would be high and plenty to keep the mill running. But there were also dry years when the lakes would be too low to furnish sufficient power. It was during one of these periods that a steam engine was installed, and water power was never used again.

The milling proved profitable for quite a while, but in time larger mills were built in the cities, and due to the competition, the small ones had to be discontinued.

One of our nearest neighbors was an Irish family by the name of Bowman. Other than the Bowman family, we were surrounded by Scandinavians, with one exception: Joe Marcott, a Frenchman, who had married a Norwegian woman and had a very large family.

Joe had never gone to school of any kind in his life. He could neither read nor write but had learned to sign his signature. Someone had made him a copy of it, and he had practiced until he could do a pretty fair job of it.

Joe was not much of a farmer but made up for this in other ways. He was handy with tools and was a good carpenter, so his services were always in demand throughout the whole neighborhood.

The Scandinavians who came over from the old country brought practically nothing more than a willingness for hard work. They were all very industrious. The first thing they did was to homestead a piece of land, building some sort of a home on it and clearing off the timber, little by little, so that it could be planted to a crop. Wheat was usually the first crop, as that was usually easy to convert into the much needed cash.

The house was sometimes built of logs. Oftentimes, it was nothing more than a so-called dugout, made by digging back into a hill and using any available material for sides and roof. There was one door and perhaps a small window in the front. Sometimes the bare ground would be the floor, and the roof would be covered with sod. It would have to do until a real log house could be built. Those who lived in a dugout for a time often got what was called consumption [pulmonary tuberculosis: "TB"] and died. The first shelters for the farm animals were built in much the same way.

As the settlers prospered, they built better buildings of either logs or lumber, and that was where Joe Marcott was in demand, especially when it came to putting up the barn. A stone foundation was built first. Then the frame for the four sides would be laid out and put together, flat on the ground. It would be built of the native timber that had been hand hewed and squared, then fitted and fastened together with wooden pegs.

When all four sides were completed, there would be a barn raising. Anywhere from 25 to 50 or more men -- depending on the size of the structure -- would be called on from the surrounding neighborhood to help. No one ever got paid more than the big feed provided by the women.

There was nothing in the way of equipment, and the whole thing had to be done by hand, under the supervision of Joe Marcott. As the sides were raised on the stone foundation, the corners were also secured by wooden pins, which were usually 1-1/2 inches in diameter. The holes to receive the pins had to be bored with a hand auger.

The raising always had to be completed in one day, and so sometimes lasted from early morning until late at night. The log houses were usually built log by log and did not need so many men at one time.

Even though Joe Marcott had no school education, he did have an eye for business. A small sawmill located in the town of Alexandria, about 35 miles away, had burned down. Joe made the suggestion to Father that he go there and buy the iron parts left from the fire. They would not cost much, and he would rebuild the wood part of the mill. With the mill engine to supply power, they could then saw the farmers' logs into lumber, either for a cash price or for exchange in lumber.

Father agreed to it, and by the next winter, Joe had everything ready for operation. For the next three years, farmers brought their logs to be sawed into lumber. Those that could afford to, paid a fixed fee per thousand feet. Others shared by giving half of the sawed lumber for pay.

Each farmer's lumber was stacked in a pile by itself. Father, with his pad to figure on and Joe with a rule to measure, would go around and measure the amount of footage in each pile. Father would get provoked because before he could figure the footage on his pad, Joe would come up with the correct answer by nothing but mental calculation. He seldom was wrong, and no one knew how he did it.

It was customary for neighbors to share the expense when it came to building joining line fences. Joe's farm joined a neighbor's, by the name of Torgerson. [This is confirmed by a plat of Eagle Lake Township in 1884, which shows all the boundary lines.] They needed a line fence in order to separate their cattle. Joe tried to get Mr. Torgerson to join in the expense of building the fence or to agree that each would build half. Mr. Torgerson refused to do either, thinking that Joe would have to do it by himself. That was just what Joe finally had to do.

Much to the disappointment of Mr. Torgerson, Joe put his fence the entire length -- but one rod [16 feet] inside the line. He then dared Mr. Torgerson to let his cattle trespass on that rod of his property. Mr. Torgerson then had to go ahead and build a fence of his own. That one rod strip was never used until after Joe sold his farm.

Joe was a frontier man and loved the wild woods. When the country began to get filled with settlers, he sold his farm and moved into new country, taking the sawmill with him. Everybody regretted to see him go.

The Scandinavians all worked hard, and as soon as one could save enough money, he would buy a ticket for some relative in the old country to come to America. The new arrival would immediately start homesteading a piece of land that had already been located for him. He, too, in time would be sending tickets for more newcomers. In that way, the country was developed very rapidly.

The new immigrant could not make a living on a raw piece of land; he also needed to have a job that would provide money. As soon as possible, he needed to buy livestock: cows for milk, a few pigs for a start, and also a small flock of sheep. To a large extent, the animals could live off the natural grasses.

No time was lost in matching up and training a pair of steers for a yoke of oxen. These may have been somewhat slow, but they were strong and dependable for farm work. In time, the oxen were replaced with horses. Horses would travel on the roads much faster and were much prized by all who could afford them.

The sheep not only were used for a meat supply, but also were sheared for the wool. No matter where one went, in every home, there was a spinning wheel. The wool would be spun into yarn. Many times I used to see Scandinavian women knitting while walking along the road to pay a visit to her neighbor. They never seemed to miss a stitch.

Those seeking a job considered themselves fortunate to work at our place because, by doing so, they were not only paid wages, but, because we spoke only the American language, they soon learned to talk it, too. One hundred dollars a year with long hours was often considered a lucky deal.

I recall when Father hired a man for ten dollars per month during the winter to cut wood and care for the stock. Shortly after that, the man's brother asked for a job. Father did not feel that he could afford to hire another man. The fellow then offered to work for his board. No doubt he needed it, and Father took him on. He put in a full day's work aside of his brother and myself and was very happy about it. He was a willing worker, and when spring came, he had no trouble finding a better paying job.

In those early days, it was quite common for the settlers to cling to their native language. Especially was this true among the older people. The Swede and Norwegian languages were much alike, but each nationality would have their own school, while in the German settlements, it would be German. As a child, Mother spoke both German and English. But she definitely made up her mind that her own children were to be Americans and absolutely refused to speak German to anyone, not even to Father. He just had to talk English, though he never did overcome his German accent.

South of us there was a German settlement, and occasionally one of them would come to the mill. On those rare occasions they would speak German, and I would be much confused. It was not uncommon for the customer to be asked in for dinner. If the customer spoke to Mother in German, she would answer in English, and I still did not understand what it was all about.

As soon as the raw land was cleared of the trees and stumps, it was planted. The main crop would be wheat, as that was the quickest to be converted into the much needed cash.

In the very early days (before my time), the wheat was cut by hand. In time, the self binder, which not only cut the grain but tied it into bundles, was invented. A second man followed the binder, picking up the bundles and setting them up in what was called a shock.

The next step was to load the shocks onto a wagon and haul them to some centrally placed stack. Frequently, there was rivalry as to who could build the nicest looking stack. It was not always the nicest formed that was the best.

The stacks started at a center point and built round. The idea was to keep the center well packed and high, with the outside row of bundles pointed down toward the outside. By that method, when it rained, the water would have a tendency to run off instead of settling on the interior of the stack and causing the grain to rot before it could be threshed. Those outside bundles had a tendency to slip out if not properly bound in. If placed too flat, the water would not run off.

There was quite a trick in pitching off a load to the man doing the stacking. Each bundle had to be placed with the head pointed toward the stacker so that it would not have to be tuned, thereby losing time. That necessitated that each bundle had to be slightly changed as the stacker moved around in a circle. It so happened, that was my job, as Father did the stacking. I managed it pretty well until it got to the very top where it was really high. Then it was up to him to catch them as best he could, and no complaints.

The crops such as wheat, oats, rye and barley were all handled in the same way. All the grain remained in the stack until the threshing machine came around. The threshing machine was owned by certain individuals who went from place to place and usually charged a certain fee per bushel threshed.

The early rigs were small and run by horsepower. From the single revolution made by the eight horses, this machine had to be geared up rapidly in order to produce the desired speed needed for the threshing machine known as the separator. A boy sat in the center with a long whip that he used to wake up any horse that decided to ease up.

Each farmer had to arrange to have the twenty-five to thirty men necessary for the threshing job. This was accomplished by exchanging help with the neighbors. The horsepower was later replaced by a small steam engine on wheels and pulled from place to place by a team of horses. Water necessary to make steam could be had from any lake or stream and was hauled to the engine in a tank-wagon drawn by a team of horses. When the first engine appeared, it was Joe Marcott who was employed to instruct the young fellow who was to become the engineer about how to operate and care for the engine.

Next came the traction engine that traveled on its own power, that is, if it did not get stuck in sand or a mudhole. The traction engine usually burned straw for fuel.

Improvements were gradually made in the separator, too. The self-feeder did away with two-man feeders. (Only one man fed at a time, but the work was rather strenuous, and the men had to change off to relieve each other.) The straw carrier was replaced by a blower, thus eliminating five or six more men. Other improvements have been put to use since my time on that job, and it was far from the present, modern way.

It would be unfair not to mention that it fell to the women to satisfy all the big appetites at threshing, which meant the butchering of a farm animal of some kind. Somehow we always managed to get plenty to eat. Breakfast was served early enough so that the men could be on the job by daylight. About nine a.m. there would be a break for what was called coffee, when the women would bring coffee, sandwiches and cake to the job. At noon the work stopped long enough for everybody to go to the house for a real meal. In the afternoon there was another break for coffee, similar to the one in the morning. From then on, work continued until dark. By that time the final meal of the day was ready to be served in the house.

In those days, one was not paid by the hour but by the day, and it was usually a full day. I can remember when seventy-five cents was the going wage. At times, when it was tough, it dropped as low as fifty cents. If it got as high as $1.50, you could consider yourself in clover.

Grain stack built to shed rain, left; rotating separator powered by four teams of horses threshes grain, right. A boy with a whip is at the hub.

The cattle that the early settlers had were not of a very good grade and were usually referred to as scrub cattle. To improve our herd, as well as those of the neighbors, my father purchased a registered Durham [Shorthorn] heifer and bull. The bull was registered in the name of Duke.

We had a pasture near the home buildings where the cows were kept in the summer, so they would be close by for milking. Another pasture, located farther away and between two lakes, was used for the other stock, including Duke. There was considerable timber in that pasture, and Father occasionally used to go there to inspect the herd to see that they were doing all right.

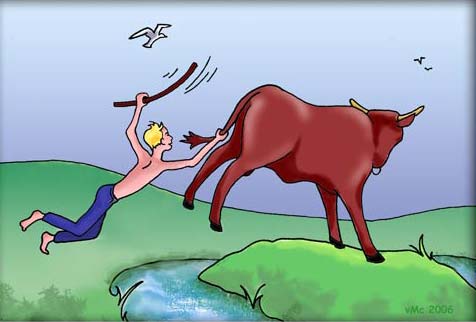

On one of these trips he found the herd but Duke was missing, so he started to look for him. He found the bull in a clump of timber, all by himself. Duke was usually very gentle and friendly. For some unknown reason, this time, he was in an ugly mood. When Father approached, Duke let out a beller [bellow] and charged. Father just had time to dodge behind a tree and lost no time in climbing another one nearby.

In time, Duke probably decided, "What's the use?" and meandered off, so Father came home. At the dinner table that evening, he told what had happened and warned me to be careful. He told me that if Duke ever charged me to climb a tree or run out into the lake.

Even though Duke was usually gentle, I never trusted him. Whenever I was around where he was loose, I would have a pitchfork or a club of some kind to defend myself.

A pair of colts took a delight in chasing the other animals whenever they felt like it. I recall one winter day when Duke was standing by himself near the corner of the barn where the sun was nice and warm. He was minding his own business and quietly enjoying the sunshine when one of the colts came tearing around the corner, expecting Duke to do as all the others did and scramble to get out of the way.

Not Duke. He stood quietly, never making a move. The colt stopped on all four feet, immediately whirled and showed his heels. Duke waited a second, then took a step forward and, with one horn in that colt's flank, raised him off his feet. That settled then and there who was boss of the barnyard.

In the spring of the year, when Duke began to shed his winter coat of hair, he had a habit of easing his head between the barb [barbed] wires of the fence and rubbing the lower part of his neck where the hair was long and thick. I suppose it itched, and the barb wire felt good. He usually managed to get the wires well loosened up and sometimes even broke them.

On one of these occasions he saw the neighbor's cattle bunched up along the side of their pasture fence, across a grass meadow and plowed field. After he had broken the wire, he decided to go on through and pay them a visit. Over the meadow, where there was grass, the frost was only slightly thawed, but on the plowed ground the frost was out six or eight inches.

Father asked me to go and bring Duke back home. He warned me to be careful, as he might be a little ugly. I picked up a piece of gas tubing about thirty inches long and went after him.

When I got there, Duke was too busy introducing himself to his new acquaintances to pay any attention to me. I walked up behind him and took a good, firm hold of the end of his tail. He was pointed in the opposite direction from me when I let fly with my piece of gas pipe. He lit out at once and made a half circle toward home, with me on the end of his tail. I managed to get in a few whams but had to ease up, due to too much speed.

As soon as we hit the plowed field and the going got tough, he slowed up, and I could get in another wham or two. That speeded him up again. This was repeated until we got to the grass meadow, where he was able to make better time.

I had all I could do to hang on until we reached a creek that zigzagged back and forth, ahead of us. With the first jump, he cleared it in good shape, with me still hanging on. When the creek zigzagged back, he managed to jump it again, but not so well. But he just wasn't synchronized right the third time and landed square in the creek, with his head resting on the farther bank, and I on his back.

It had been some time since I had got in a wham. This was my last chance, and I whammed away. It put him out of the creek and on his way through the fence, into his own corral, leaving me in the creek.

Duke did not bother to go back through the break in the fence that he had made on his way out but hit a new spot, not stopping for the barb wire, but making a new break. He went straight to the straw pile and lay down for a rest.

I did not know what to expect from my father but was relieved to see a sort of grin on his face. The only thing he said to me was, "You know that bull cost a lot of money, and you must not hurt him."

I spent the balance of the day repairing the fence.

Photo illustration © Virginia McCorkell

Duke clears the creek with young Edward hanging on...

Sometime about the latter part of October or early November, the numerous lakes would freeze over, an indication that winter had begun. As soon as the ice was thick enough to be safe to go on, there would be skating parties nearly every evening. This would last until the first snow came. Some years, it might be several weeks before the ice was covered with snow. Other years, there might be an early snow, and the ice skating season was cut short.

With the snow came the time for skiing. Instead of being called skis, they were always known as snowshoes, although the real snowshoe is an entirely different thing and used for walking on top of loose snow. Every Scandinavian boy had a pair of snowshoes, but I did not. An old gentleman had an extra pair that he had made and offered to sell them for one dollar. I wanted them in the worst way, but I did not have the necessary dollar. He finally lowered his price to seventy-five cents, which I thought was reasonable, but still did not have. I made up my mind that I had to have a pair of snowshoes, somehow. The only way possible, that I could see, was to make a pair myself.

I went out into the woods and hunted around until I finally found a tree that suited me. It was a birch tree, tall and straight and about 4-1/2 or 5 inches in diameter. I cut it down, carried it home and secured it in a wooden vise on the work bench. I had to rip it straight down through the center. There was no such thing as a power tool to do the work. All I had was a two-man, crosscut saw. By standing on top of the bench, I could pull the saw up and then push it down.

It was a slow way, but little by little, I succeeded. It was a long way from the starting end to the far end. After several days, I finally finished and had two halves with the flat sides fairly straight. By that time, spring was beginning to set in, and there was no hope of having them to use that winter. But there would be another winter coming.

The next step was to get the two pieces shaped into boards about 3/4 of an inch thick and 3-1/2 inches wide. I took off the worst of the round side with an axe and finished up with a draw knife. The finished job on the sides and edges was done with a jack plane. That finished, I thought I had two pretty good pieces, but I was still not done. A difficult job was still ahead of me; that was to bend the two front ends.

The material was still green, which would be of some help, but I let the two ends to be bent soak in water for a few days. I cut a notch on the bottom side near each end to be bent. The next step was to place the two pieces with bottom sides facing each other and with a cord around the rear end to keep them in that position. Next, I put a short piece about 9 inches long between and just back of the notches on the front end. That gave a wedge shaped space between the two pieces.

About 12 or 15 inches back from the front end, I wrapped a straight cord, drew it as tight as I could, and tied it. Using another cord next to it, I managed to draw it a little tighter -- then back to the first cord to draw it up a little more. By repeating the operation several times, the two bottom edges were brought together.

By this time it was spring, and warm weather had come. There was no need for snowshoes that season, and I laid my two pieces away to dry out during the warm summer. By the time fall had come, my two pieces would hold their shape, and with a few finishing touches, I would have a pair of snowshoes.

It so happened that the coming winter brought an unusually heavy snowfall, and I made good use of my snowshoes in travelng the 2-1/2 miles over deep drifts to the country school.

SCHOOL DAYS

by Edward W. Miller

Ontario, CA

I continued to attend the one-room school during the winter months until I was eighteen years of age. My mother was determined that her children were to have as much of an education as possible, but my father was not concerned about it at all. Mother managed to arrange for my two sisters and myself to continue on to school in Fergus Falls, which was a distance of about twenty-five miles from our farm.

The girls would get to start at the beginning of the term and remain through to the end. I had to remain on the farm until all the fall farm work was done. Then, when spring came, I had to drop out from school in order to help put in the crops. That gave me somewhere from four to five months in the middle of each school term.

I spent a few months in the seventh grade in Fergus Falls and the following year was admitted to the eighth grade. I was eighteen years old by that time, and Amelia, two years younger than I, was well along in high school.

We rented rooms and boarded ourselves. Most of the produce we needed came from the farm. My mother made many long, hard trips to keep us supplied. The only method of transportation was by team and wagon.

In order to earn money to help out with expenses, I used to spend Saturdays sawing wood that was used for fuel. I would saw a cord that came in four-foot lengths into three pieces, for which I was paid from forty to fifty cents. With a hand buck-saw it was an all-day job, beginning at daylight and lasting until dark.

After spending half sessions for two years in the eighth grade, I was pronounced eligible to enter high school, but I never did. My two sisters did and graduated with honors.

A small business college had started up in Fergus Falls, and my father decided that was the place for me. I wanted to go to high school but was compelled to spend two short terms at the business college.

By the time that was over, my sister Amelia had graduated from the high school [in 1904], and with the help of my mother, I was permitted to go with her for a short summer session at the normal school [for teacher training] in Moorhead, Minnesota. We again rented rooms and boarded ourselves. By the skin of my teeth, I did get a credential that permitted me to teach in a one-room, country school similar to the first one I attended.

There were two [school] terms: first, one of three months, then a break during the coldest month, and another four month term. The school board told me that they preferred to have a man teacher because the two previous lady teachers had too much difficulty managing some of the big boys.

For the first three months' term, I received $20 a month and paid my own room and board. I managed to persuade the clerk of the school board to take me in, for which I paid them $5 per month for board and room. I applied for the second term but upped my price to $25. By that time I had not only gotten well acquainted with the clerk's family but also with the Mrs.'s younger sister, whose family lived on a farm not too far away. I don't recall her name and doubt that I would know her if I saw her, but we did have some happy times together.

Like most other farms, there was a barn where the farm animals were kept and the winter supply of hay was stored. Mr. _ had intended to have a sling installed to unload hay. It would be carried on a track located in the peak of the barn and would be operated by a rope, to which a team of horses was hitched. I told him that if he would furnish the necessary material, I would build the overhead track and install the equipment. I did the job on Saturdays, and by so doing, paid for my board and room.

In the meantime, I got in touch with the Metropolitan Business College in Minneapolis and received an offer to teach in one of their branch schools. As soon as my country school had closed, I went to the Minneapolis school to brush up on commercial work, as I had made no use of it after leaving Fergus Falls.

It was while I was in Minneapolis that an attorney from New Ulm, Minnesota, called at the school to get a young man to work in his law office and study law. Someone in the school recommended me. The lawyer said if I would come, he would make an attorney of me. I did not accept, and maybe that was one of my numerous mistakes.